Encyclopedia Of Detroit

Uprising of 1967

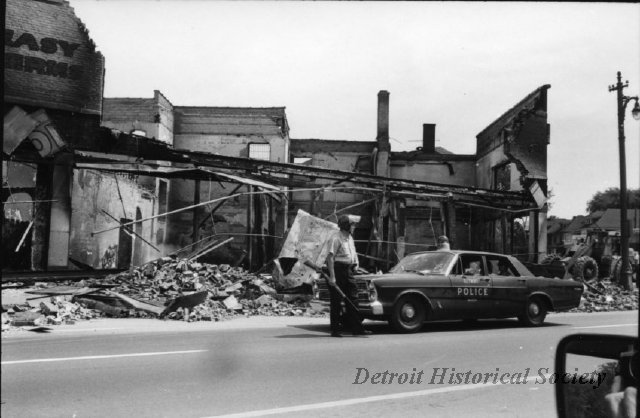

The Uprising of 1967 is also known as the Detroit Rebellion of 1967 and the 12th Street Riot. It began following a police raid on an unlicensed bar, known locally as a “blind pig.” Over the course of five days, the Detroit police and fire departments, the Michigan State Police, the Michigan National Guard, and the US Army were involved in quelling what became the largest civil disturbance of twentieth century America. The crisis resulted in forty-three deaths, hundreds of injuries, almost seventeen hundred fires, and over seven thousand arrests.

The insurrection was the culmination of decades of institutional racism and entrenched segregation. For much of the twentieth century, the city of Detroit was a booming manufacturing center, attracting workers—both black and white—from southern states. This diversity aggravated civil strife, and the Race Riot of 1943 highlighted the racial fault lines that crisscrossed the city. Throughout the 1950s, homeowners’ associations, aided by mayors Albert Cobo and Louis Miriani, battled against integrating neighborhoods and school.

Deindustrialization within the city limits took many jobs to outlying communities, even as a number of auto companies went out of business. The east side of Detroit alone lost over 70,000 jobs in the decade following World War II. Construction of the city’s freeways, newer housing, and the prospect of further integration—due to the demolition of the city’s two main black neighborhoods, Black Bottom and Paradise Valley—caused many whites to depart for the suburbs. From 1950 to 1960, Detroit lost almost 20 percent of its population.

Virginia Park rapidly transformed from a predominantly Jewish neighborhood to primarily black neighborhood by 1967. The new epicenter of black retail in Detroit became 12th Street (now called Rosa Parks Boulevard), a strip which also supported a lively illicit nightlife. Adding to tensions was the black community’s fractious relationship with the mostly white Detroit Police Department. Like many forces across the country, the department was known for heavy-handed tactics and antagonistic arrest practices, particularly toward black citizens.

At 3:15am on July 23rd, the vice squad of the Detroit Police Department executed a raid on a blind pig at 12th Street and Clairmount. Despite the late hour, the avenue was full of people attempting to stay cool amidst a stifling heat wave. As the police escorted party goers to the precinct for booking, a crowd gathered and the situation grew increasing antagonistic. When the final arrestees were loaded into police vans, a brick shattered the rear window of a police cruiser, prompting a rash of break-ins, burglaries, and eventually arson.

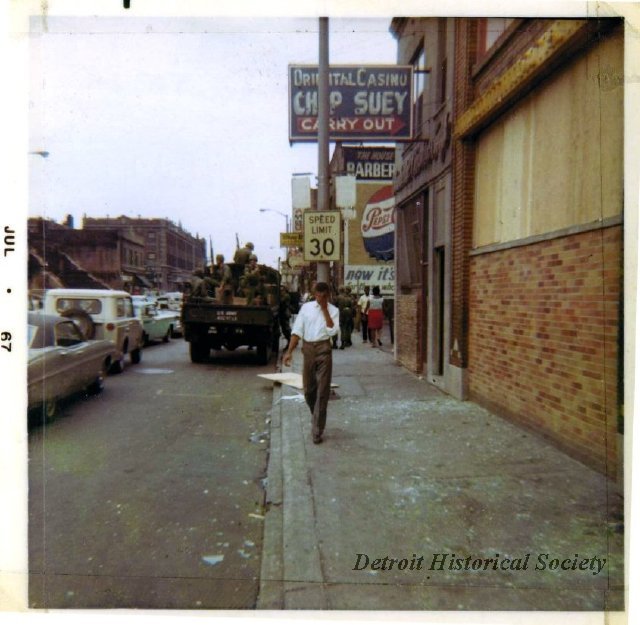

Law enforcement was immediately overwhelmed. While the department had 4,700 officers, only about 200 were on duty at that hour. Early efforts to regain control failed and a quarantine of the neighborhood was imposed. Hoping to ease tensions, Mayor Jerome Cavanagh ordered that looters not be shot; as the word of his order spread, so did looting. The Michigan State Police and the National Guard arrived to reinforce police and fire units. Clashes between the mayor and Governor George Romney—both of whom had presidential aspirations—and President Lyndon Johnson increased confusion and delayed the deployment of federal troops.

By the end of the first two days, fires and looting were reported across the city. Additionally, the mass theft of firearms and other weaponry turned Detroit an urban warzone. Sniper fire sowed fear and hindered firefighting and policing efforts. The arrival of battle-tested federal troops on Tuesday, July 25th brought order.

For many people the uprising was a turning point for the city. White flight in 1967 doubled to over 40,000, and doubled again the next year. Yet, many Detroiters remained. The city saw a massive growth in activism and community engagement. New Detroit and Focus: HOPE were both founded in the aftermath, with the goal of addressing root causes of the disorder. As the city’s demographics continued to shift, Detroiters elected the first black mayor in the city’s history, Coleman A. Young.