An Inventor Ahead of His Time

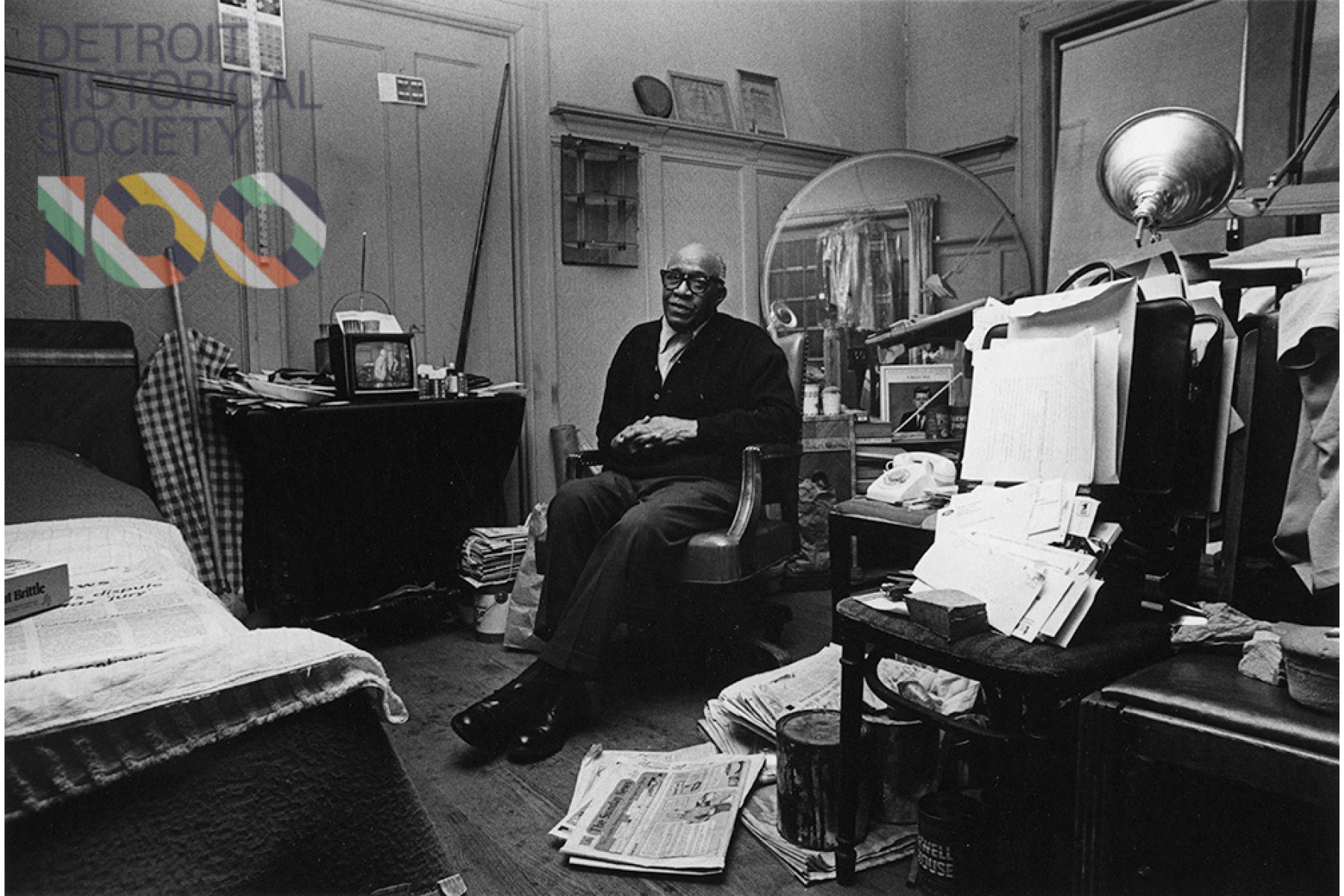

In a photo dated 1973 from our collection titled “Owner of West End Hotel,” a nearly 79-year-old African American man sits for a portrait in his room in the titular hotel in Detroit’s Delray neighborhood. His hands are folded, and his head is tilted. The items in the room provide tantalizing potential clues to this mysterious man’s life—a stack of newspapers, a record of President Kennedy’s speeches, a briefcase filled with documents, and a drafting table. However, the assumptions one might make from these scant details would surely fall short of the truth of this man’s story.

The subject of this photo is Joseph N. Blair, who not only put the West End hotel on Detroit’s musical map, but also invented new concepts and materials in areas ranging from prefabricated building materials to rocketry!

First Inspirations

Blair was born in Augusta, Georgia in 1904. Details about his education are conflicting—early newspaper stories perhaps sensationally noted that he did not finish seventh grade, however later profiles stated that he attended Paine College for two years before heading north in search of work. After a stint in construction, he found employment with Ford in their foundry in the 1920s. During this period, he also developed an interest in artillery, which inspired him to design an anti-aircraft gun combined with a spotlight for sighting targets. He went on to draw up plans for submarines and two-stage artillery shells that pre-figured the rockets that would soon play a significant role in World War II. In 1928, he presented these ideas to the U.S. Navy in Washington D.C., but as he later recounted to the Detroit Free Press, he and his proposals were not taken seriously. While Blair’s ideas may have been ahead of their time, it was racism that prevented those around him from acknowledging Blair’s groundbreaking work.

A Variety of Inventions

In 1943, Blair appeared before the National Inventors Council, a wartime organization interested in inventions with military application, and showed his plans for a V-2-like rocket. The ideas he had been developing dated back to the 1920s. While the story made headlines in the famous Pittsburgh Courier, Blair and his designs were again ignored by the military. However, in 1958, with the Cold War and the space race giving renewed immediacy to the science of rocketry, Blair tried once again, presenting his ideas to the Department of Defense. Here at last, Blair and his rocket designs were taken seriously. Jet magazine covered this meeting and wrote of one official asking Blair why he did not meet with them twenty-five years sooner, to which Blair replied, “Sir you know why—don’t make me say it.”

In addition to reaching for the stars, Blair also applied his ingenuity to immediate earthly concerns. Perhaps not surprisingly, Blair actually built a better mouse trap. In 1947, he filed a patent for a design made to fit below garbage cans. This plan featured multiple traps, arranged in a ring around a central common bait chamber. He also tackled the issue of affordable and easily manufactured housing, in a project which would bring him into the orbits of world leaders.

In October of 1962, Blair filed a patent for a design for interlocking blocks that would secure together through a combination of grooves and pegs without the need for skilled masonry work. These blocks could be cast on-site using readily available clay. Former Michigan Governor G. Mennen Williams, who was at the time a member of the Kennedy Administration as the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, vouched for Blair’s idea and saw it as a potential foreign policy tool akin to the brand-new PeaceCorps. In December of that year, Blair traveled to Tanganyika (now part of modern-day Tanzania) to meet with their president and to propose that his interlocking blocks could help modernize the new nation. Unfortunately, the plan was not adopted, something the Free Press later chalked up to “bad luck and bad advice.”

The West End Hotel

In the late 1940s, Blair left Ford in order to go into business for himself and to retain control of his inventions. As owner of the West End Hotel, Blair took on a surprising new role in Detroit’s musical history, but that of course didn’t mean that he stopped inventing. In fact, he continued filing patents while working from the hotel, which he managed with his wife Georgia. His designs for the interlocking blocks come from this era, as did a design for a reversible window where the outside panes could be cleaned from the inside, something very practical in his line of work.

And while the Blairs were certainly working hard, they also knew how to have a good time. During the 1950s, their West End Hotel became an after-hours spot for both local and touring jazz musicians. The Blairs ran a clean establishment, and drinking and gambling were strictly out at the West End, so music was the focus here after all the other clubs had closed. On one memorable early Tuesday morning, Detroit’s Yusef Lateef bonded with Sonny Rollins over a session at the West End. In Lars Bjorn and Jim Gallert’s book Before Motown, drummer Hindal Butts recalls that this unlikely afterhours spot sprung up because Georgia Blair’s health made going out difficult, so instead these sessions were a way of bringing what she’d be missing to her doorstep.

Later newspaper profiles and even notes from our own past curators recount visits to Joseph Blair’s apartment in the West End as stepping into a treasure trove of drawings and models of his many inventions. It was one such visit which likely inspired Terry Yank, a photography student of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies), to take our portrait of Blair in 1973. Blair passed away in 1984 but stayed busy during those final years. His last patent—a new version of his reversable window design—was filed with his daughter Mamie in 1981.