Looking Back at 1967 at 24 Frames per Second

Soldiers watch as flames swirl and rise from storefronts along the southwest side of 12th Street, near Taylor Street--one block away from where, days earlier on July 23, 1967, an early morning police raid sparked the unrest.

Soldiers watch as flames swirl and rise from storefronts along the southwest side of 12th Street, near Taylor Street--one block away from where, days earlier on July 23, 1967, an early morning police raid sparked the unrest.

In late July of 1967 as Detroit erupted, former police beat reporter Edward T. Breslin grabbed his 16mm movie camera, and utilized his old connections to get some incredible footage. In preparation for our new exhibit Detroit 67: Perspectives, we sought previously unseen photos and film depicting the city during the turbulent summer of 1967, and Breslin’s footage is among the most significant of the new discoveries. Breslin’s family kindly reached out to us last year, and donated a DVD transfer of the footage. We were so taken with what we saw that we worked with the family to do a fresh high definition transfer of the film. The resulting twelve minutes of video are now part of our Detroit Video History Archive.

A man stops to pose for a photographer and for Breslin's film in front of the remains of a building on the west side of 12th Street between Hazelwood and Taylor Streets.

A man stops to pose for a photographer and for Breslin's film in front of the remains of a building on the west side of 12th Street between Hazelwood and Taylor Streets.

In 1967, Edward Breslin worked in Chevrolet’s public relations department, where he had a reputation as a practical joker. In his previous career, however, he had worked as a reporter and a photographer covering crime for the Detroit Times and Detroit Free Press. When the unrest of that summer broke out, Breslin’s old reporter instincts kicked in, and he set out with a camera in hand. His footage attests that he still had contacts in law enforcement; during the course of the film, Breslin shoots from the police line along 12th Street, rides in a helicopter above several massive plumes of smoke, and tags along in a military vehicle during a night time patrol. He’s also present as Wayne County sheriffs search a car and frisk its occupants, and his camera rolls as firefighters work to put out several blazes. His most striking footage may his nighttime footage of silhouetted troops watching as orange flames swirl from the husks of burning buildings.

Armed guards are stationed on Belle Isle's beach beside the bath house. During the unrest, the bath house was used as a make-shift jail.

Armed guards are stationed on Belle Isle's beach beside the bath house. During the unrest, the bath house was used as a make-shift jail.

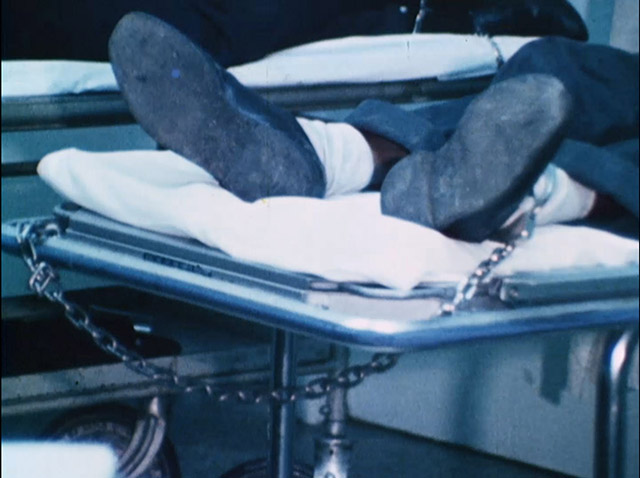

While Breslin shot plenty of street footage of crowds, smashed storefronts, and fire-damaged buildings, his most unique footage likely comes from several of the special locations he visited. At St. Gregory Parish, Breslin found a long line of neighborhood residents waiting for groceries distributed by the nuns within. Here, a Boy Scout can be spotted walking along the line, distributing neckties. Downtown at police headquarters, Breslin films a group of arrestees climbing out of a crowded police truck. He then moves to a waiting room inside where several of the handcuffed men appear to wave to the camera. With the numbers of arrestees exceeding capacity for traditional incarceration, authorities began housing prisoners on city buses and in Belle Isle’s bath house. Breslin’s film reflects this with a series of shots showing a city bus arriving at a make-shift checkpoint beside Belle Isle’s beach. In the following scenes, officers stand by as a row of men file past stations where they receive blankets. Perhaps the film’s most powerful moment comes as part of Breslin’s visit to Detroit General Hospital where his camera lingers on the chains that keep several patients handcuffed or shackled to their hospital beds.

A patient at Detroit General Hospital is shackled to his gurney.

A patient at Detroit General Hospital is shackled to his gurney.

Edward Breslin’s film, as well as nearly 600 newly digitized photos of the unrest can now be viewed through our Online Collection. This material, combined with our growing Oral History and Written History project database forms a web-based wealth of information supplementing Detroit 67: Perspectives. The exhibit is open now at the Detroit Historical Museum.