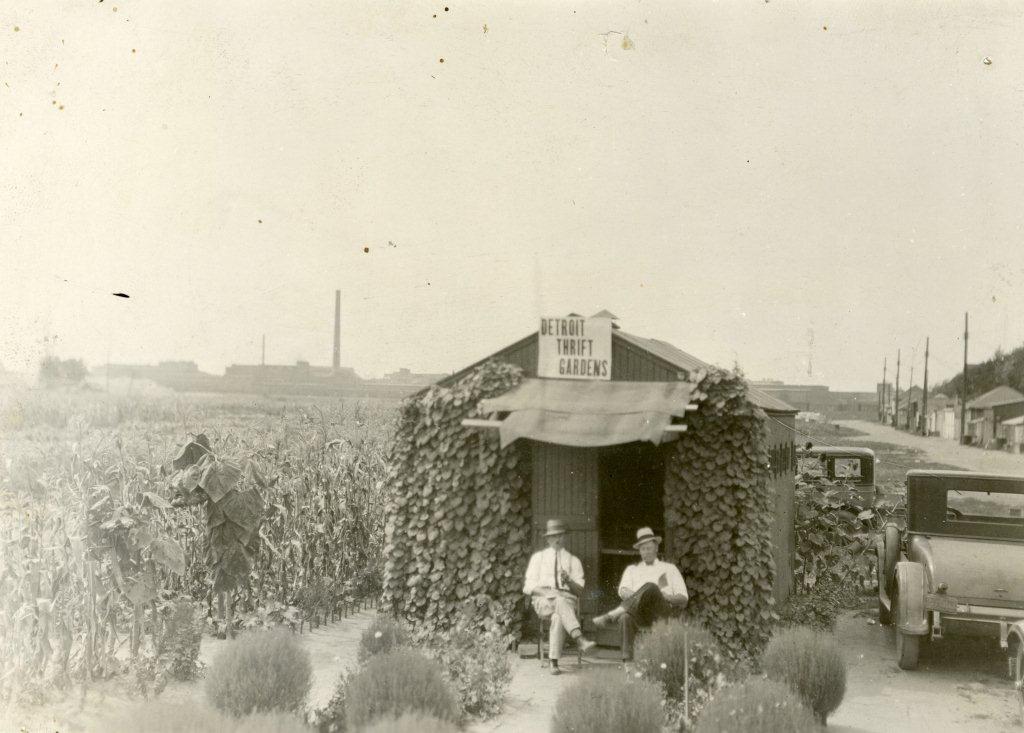

Detroit’s current availability of vacant land has made it a popular place for urban farming, but this is not a new phenomenon brought about by abandoned neighborhoods and diminishing population. During the Great Depression, Mayor Frank Murphy suggested a program that would eventually become the Detroit and Wayne County Welfare Relief Administration’s Thrift Garden Project. Started in 1931, it sponsored vegetable gardens for both “families in relief” and “needy borderline families”.

Garden records were kept by a supervisor and field overseer who made note of the condition of gardens.

Garden records were kept by a supervisor and field overseer who made note of the condition of gardens.

Households applied to be included in the program and could either have a Home Garden in backyards or adjacent vacant lots, or receive a plowed 40 x 100 ft. designated plot in one of the large Field Gardens on donated land about the city. Gardeners were issued commercial fertilizer, tomato and cabbage plants, and seeds for many vegetables including radish, beets, kohlrabi, swiss chard, kale, squash, turnips, okra, and parsley furnished by the State Emergency Welfare Relief Administration. To assists the gardeners, tools could be borrowed at each field office and stockyard manure was applied to especially deprived fields. Insecticide was also made available and canning demonstrations and supplies were offered. Michigan State College provided informative bulletins to the gardeners.

Gardeners were not allowed to sell their produce, and if assigned to a Field Garden, they had to agree to serve occasionally as a night or day watchman to protect against theft. Field overseers were made special officers by the Police Department and given whistles, badges and the authority to make arrests, though few attempts were made to steal produce. The biggest problems were transportation and weather. Many gardeners had to travel long distances to reach a Field Garden using public transit or hitchhiking. Lacking proper irrigation systems, rain and drought hindered production, and in 1932 the corn crop was wiped out by Stewarts’ Wilt.

To promote and publicize the project, educational exhibits were displayed at the Horticultural Society of Michigan’s Fall Show, the Michigan Agricultural and Industrial Exposition, and the Michigan State Fair. Radio broadcasts and lectures in public schools touted the program, and a Spring Festival at the Masonic Temple raised money for the Thrift Gardens.

By 1935, the project had expanded to include the whole county, except Dearborn which ran its own program. Surveys showed that everyone enjoyed working their garden and that the average garden value was $35, but some were as much as $100. The Project Commission determined that “Fresh air, sunlight and the visible results of their own work have altered the morale of many gardeners. The mental, physical and social rehabilitation of the individual gardeners is perhaps as important an aspect of the Thrift Garden Project as the financial benefits.”